Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire Where on Netflix

Let's do a casual experiment. Here's a brief passage from the first book in some obscure fiction series called Harry Potter:

A bush on the edge of the clearing quivered. … Then, out of the shadows, a hooded figure came crawling across the ground like some stalking beast. Harry, Malfoy, and Fang stood transfixed. The cloaked figure reached the unicorn, lowered its head over the wound in the animal's side, and began to drink its blood.

And here's another passage from the final book of the series:

He got up off the floor, stretched and moved across to his desk. Hedwig made no movement as he began to flick through the newspapers, throwing them on to the rubbish pile one by one; the owl was asleep, or else faking; she was angry with Harry about the limited amount of time she was allowed out of her cage at the moment.

Which passage did you find more engaging? Chances are it was the first. While the second passage might advance the plot, the first passage has drama, tension, and irresistible vampire-like behavior stuffed into a matter of four lines. It's the type of action that helps readers get lost in a book. And it's precisely this ability to immerse readers that helps sell hundreds of millions of copies.

The results of our experiment, that action is more engrossing than scene-setting, may be unsurprising. But a group of psychologists led by Chun-Ting Hsu of the Free University of Berlin believe this approach, when used in conjunction with neural imaging, can help scientists understand exactly what's going on in our brains when we get pulled in by a great story. They describe just such a study–calling it the "first attempt to understand the neural mechanisms of immersive reading experience"–in an upcoming issue of the journal NeuroReport.

Hsu and collaborators recruited test participants to enter a brain scanner and read passages of Harry Potter (translated into German) about four lines long. Some of the passages were fear-inducing, like those at the top of this post, while some were neutral, like those in the second block above. (While the paper doesn't list any actual examples used in the study, the above passages seem like fair representations.) A separate group of participants rated each passage for how immersive they found it to be.

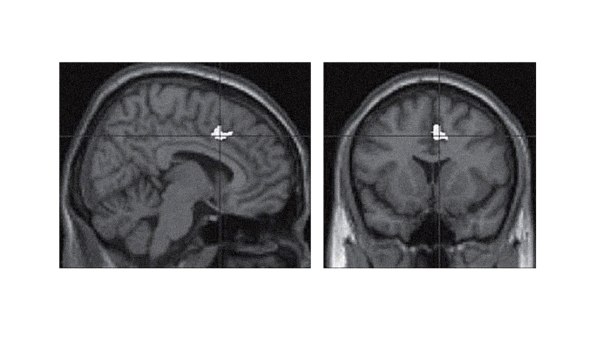

As expected, the fearful passages received significantly higher ratings for immersion than the neutral ones–more likely to get readers lost in the book. In the middle cingulate gyrus area of the brain, Hsu and company detected a much stronger link between immersion ratings and neural activity for the fearful passages than for the neutral ones. The middle cingulate gyrus is considered part of the brain's empathy network, and has been associated with pain empathy in particular.

The results support what the researchers call the "fiction feeling hypothesis" of reading immersion. Broadly speaking, the idea holds that the empathy network of a reader's brain becomes more active during emotional moments of a story, compared with more neutral or plot-driven moments. That's especially true when the emotional moments are negative, arousing, or suspenseful, according to Hsu and company. In short, fearful passages facilitate literary immersion by engaging neural empathy networks.

"Descriptions of protagonists' pain or personal distress featured in the fear-inducing passages apparently caused increasing involvement of the core structure of pain and affective empathy the more readers immersed in the text," the authors conclude.

The research makes a fine starting point for the study of immersive reading, but The Neurocritic (who spotted the paper) is right to call the results "a bit underwhelming." Hsu and company failed to find any evidence for heightened activity in the anterior insula, another part of the empathy network, which puts a bit of a damper on their "fiction feeling" theory. That might be a consequence of J.K. Rowling describing emotion vividly rather than merely labeling it, which would recruit the middle cingulate gyrus (a motor region) more than the anterior insula (a sensory region). In lesser prose they might have found another result.

But the study struggles at a more basic level, too. For one thing, most of us associate getting lost in a book with losing perhaps an hour before we know it–four lines just isn't enough space to simulate the experience. Beyond that, the brain activity spotted in this study arguably speaks much more to the type of passage chosen than to the experience of immersion, per se. Nor does a strong reaction to fearful passages say anything about the value of neutral passages; if every passage were fearful, then eventually the fearful becomes the neutral.

So this evidence might be a good first step toward understanding, through the lens of neuroscience, what makes some books so absorbing. For now, though, we might as well still call it magic.

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire Where on Netflix

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3038165/the-neuroscience-of-harry-potter

0 Response to "Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire Where on Netflix"

Post a Comment